Should we ban non-compete agreements?

One SIMPLE trick to create a more dynamic economy for workers and startups

Whether you’ve been reading Workonomics for a minute or are a new reader — welcome!

Workonomics is a publication focusing on technology, workers, and policy. I write on policy topics like AI, the gig economy, and the intersection of antitrust and labor.

A few housekeeping items. I’m switching the cadence of Roundup posts (with recent links, news, and opinions) to every two weeks and making them a bit more bite-sized. This will create more time for me to work on other posts like interviews, guest posts, and deep dives — like the one below!

As always, I’m curious to hear about the tech, labor, and policy topics you’d like to read about here in Workonomics! Feel free to leave a comment or drop a line on Twitter.

On to the post:

The FTC’s Non-Compete Proposal

The Federal Trade Commission started off the year with a ban. Or at least a proposal for one. Noah Scheiber at the New York Times writes:

In a far-reaching move that could raise wages and increase competition among businesses, the Federal Trade Commission on Thursday unveiled a rule that would block companies from limiting their employees’ ability to work for a rival.

The proposed rule would ban provisions of labor contracts known as noncompete agreements, which prevent workers from leaving for a competitor or starting a competing business for months or years after their employment, often within a certain geographic area. The agreements have applied to workers as varied as sandwich makers, hairstylists, doctors and software engineers.

Studies show that noncompetes… hold down pay because job switching is one of the more reliable ways of securing a raise. Many economists believe they help explain why pay for middle-income workers has stagnated in recent decades. Other studies show that noncompetes protect established companies from start-ups, reducing competition within industries…

Defenders of noncompetes argue that employees are free to turn down a job if they want to preserve their ability to join another company, or that they can bargain for higher pay in return for accepting the restriction. Proponents also argue that noncompetes make employers more likely to invest in training and to share sensitive information with workers, which they might withhold if they feared that a worker might quickly leave.

The FTC estimates that 30 million workers, including employees, independent contractors, and summer interns, have a non-compete agreement in their contract. It also estimates that non-competes result in $300 billion in lost wages each year.

You’re probably very familiar with some of the companies that use non-competes:

The proposed ban would essentially direct the country to follow in the footsteps of California, which has not enforced non-compete agreements since 1872. Legal scholars and historians have argued that this set the stage for the birth of Silicon Valley, given that — unlike in other states — technology workers could job-hop and start new companies without fear of gettings sued by their former employer.

We might not have Intel, Apple, or the many self-driving car companies founded by ex-Google employees if non-competes were enforced in California.

But how much will a ban on non-competes help workers? What are detractors saying, and do their arguments have any merit? What will ultimately happen in the final rulemaking? In this post, we’ll explore some of these questions.

The Case for Banning Non-Competes

To put the non-compete ban in context, the Biden administration has long argued that employers hold disproportionately more bargaining power than workers. A 2022 Treasury Department report estimated that employers’ “wage-setting” power holds back workers’ wages by 20% (compared to what they would otherwise be in a perfectly competitive labor market).

As a result, the Biden FTC and DOJ have been taking legal action to enforce competition in labor markets. For example, they have aggressively pursued employer collusion cases, blocked corporate mergers if they harm worker wages, and signaled their intent to enforce antitrust law to protect gig workers.

Banning non-competes follows as one of their steps to encourage more competition for workers. The FTC issued a 216-page report citing empirical economic studies and legal research supporting their claim that non-competes are bad for the economy.1

Here are the primary arguments laid out by the FTC and other supporters:

Increasing wages and mobility across all workers: Various studies support that non-competes harm the workers bound by them and impose a negative externality on the rest of the labor market. In other words, non-competes clog up the whole system, holding back job mobility and wages for all workers. One study, for example, estimated a nationwide ban would increase earnings for all workers by an average of 3.3-13.9%.

Increasing startup formation: Workers can more easily choose to leave and start a new business in the same industry as their former employer. Some argue that California’s lack of non-compete enforcement was a key reason Silicon Valley overtook Boston as the epicenter of the technology revolution.

Reducing consumer prices: Increasing competition in the market should also precipitate a fall in consumer prices.2 A study found this was the case in healthcare, and the FTC estimates that eliminating non-competes could reduce healthcare costs by $148 billion annually (around 3%).

There are alternatives to non-competes: The proposed rule wouldn’t affect non-disclosure agreements, which prohibit workers from discussing confidential company information outside their firm. Equity and retention bonuses can also have the same effect as non-competes by retaining talent and trade secrets at the firm, and workers can more explicitly negotiate them.

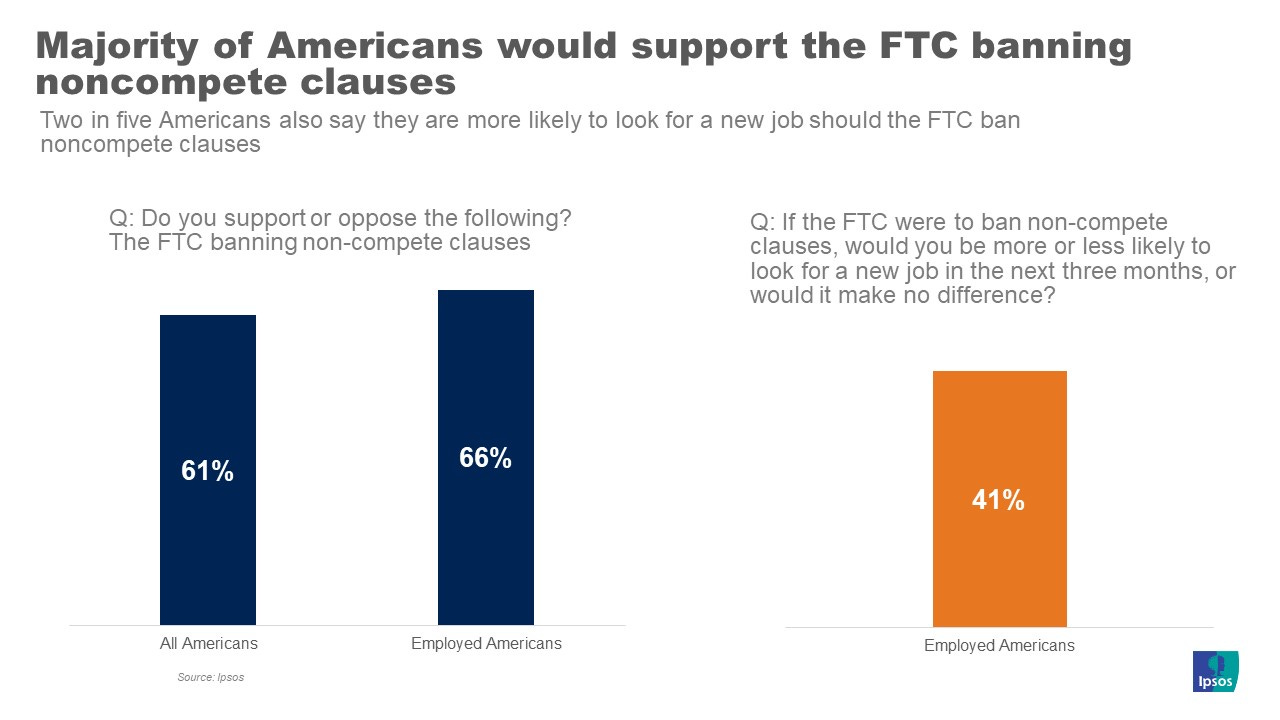

A majority of Americans don’t like non-competes: a recent Ipsos poll shows that 61% of Americans support a full ban on non-compete clauses, and 41% of employed Americans would be more likely to look for a job after a ban. This aligns with a 2021 poll by Data for Progress that shows 57% of Americans support limiting non-competes.

To summarize the FTC’s argument: to build a dynamic economy where workers have greater bargaining power and can more easily start their own companies, we need to ban non-competes. Non-competes gum up the labor market, harming not just the workers that have a non-compete but other workers as well. Banning non-competes would have positive externalities for other workers and entrepreneurs.

So is that the end of the debate? Let’s take a look at the opposing view.

Addressing the Counterarguments

The fact that so many companies still give workers non-competes should give you a sense of why there is strong opposition to the proposed FTC rule. Here are some of the big counterarguments:

We should have a partial ban, not a full one

Many proponents of non-competes admit that they are probably exploitative of low-wage workers like hairstylists and fast food workers. Many support banning non-competes for low-wage workers but believe they’re still valuable for everyone else.

These proponents point out what happened to state-level non-compete regulations. 11 states and DC banned non-competes for low-wage and hourly workers while still allowing them for other workers. Yet only three states have a full ban. So wouldn’t it be better to take the more popular approach and do a partial ban covering low-wage workers?

On the face of it, it makes sense. But here’s the problem: if you were to set an income threshold, below which you ban non-competes and above which you allow them, what would you set it at?

Looking closer at the states that set such a threshold, it varies from $30,000 in New Hampshire to $100,000 or more in Oregon, Washington state, and Colorado. That’s a pretty wide range for describing “low-wage” workers.

In Washington state, the $100,000 threshold is at the 78th percentile of income for workers. Why not set it at the 80th percentile? 90th? 95th? Why have one at all?

There’s no systematic way to determine a good threshold — $100,000 was just a nice round number for policymakers to pick. When you realize the arbitrariness of these partial bans, you might question why we would want to treat “low-wage” workers so differently from “high-wage” workers in the first place.

Yet let’s give supporters of non-competes the benefit of the doubt. For other reasons, these clauses may still be important for high-wage workers, executives, and the C-suite. Let’s take a look at those.

Firms with non-competes invest more in worker training

Supporters of non-competes argue that non-competes are net-positive for workers since the firm will invest in more expensive training because they know workers will remain loyal to the firm.

So, in this case, non-competes can be helpful for these companies to keep their workers longer and reap the benefits of those training costs. The FTC has acknowledged this is one of the benefits of companies issuing non-competes. However, just because non-competes are one option to encourage investment in training doesn’t mean they are the only or the most efficient one.

Overall, labor market dynamism may be better served by giving workers a long-term compensation package to retain them. Training repayment programs are more stick than carrot, but at least they are more transparent with workers about costs and a more targeted economic intervention than a blunt non-compete agreement.

We also shouldn’t forget that training can be provided through other sources, like individuals, unions, and the government, which have long-term investment horizons. In contrast, the median employee tenure is only 4.1 years. In reality, workers no longer work for companies as long as they used to. We should encourage funding for training from multiple sources.

Corporate training schemes are good. But they shouldn’t be done in ways that stifle worker mobility and undermine startups trying to hire talent.

Firms with non-competes entrust workers with trade secrets

Economist Tyler Cowen, who supports a partial ban for low-wage workers, lays out an example here:

Say you run a hedge fund. Many members of your trading team will have partial access to your firm’s trading secrets, and if they leave they can take those secrets with them. In the absence of noncompete agreements, firms would be more likely to “silo” information — becoming less efficient and less able to pay higher wages.

Won’t someone think of the hedge fund managers?!

Jokes aside, we can look at workers in an industry with many trade secrets — a high-tech worker in Hawaii, for instance — and evaluate Cowen’s argument.

When Hawaii passed a ban on non-competes for its tech workers in 2015, this created a natural experiment by which economists could measure differences between Hawaii relative to other non-tech workers in Hawaii or tech workers in other states. They found that income for new hires went up by 4%, and job mobility throughout the entire tech industry went up by 11%.

So it’s not like non-competes were helping these workers earn higher wages. We should ask ourselves: are non-competes the only thing we can use to ensure that trade secrets don’t leak?

Trade secrets laws exist for this very reason. It’s even alive and well in California, which has banned non-competes. Some of you may remember when AI scientist and prophet Anthony Levandowski was sent to prison for keeping self-driving vehicle algorithms from his time at Google and bringing them to Uber.

The Road Ahead

Overall, I think we should applaud the FTC for taking action to create a more competitive, dynamic labor market for workers and startups. There are downsides to a full ban, namely ensuring that long-term investments are made in workers. But there are still many other avenues to accomplish the same goal.

A friend recently told me that “the wheels of Government move slowly.” Someday I’ll get that quote framed and put it on my wall. As for the FTC proposal, we may not see a final rule issued until late 2023 or early 2024. Non-competes will stay in place for a little bit.

As part of its rulemaking process, the FTC will collect public comments until March 10. After that point, it must go through all 5,300 (and counting) submitted comments.

If you’ve ever been affected by a non-compete, or if you work at a company and wish you could hire someone who had a non-compete, or even if you’re on the other side and think non-competes are significantly better than their alternatives, I’d highly encourage you to leave a comment:

Once reviewing new comments and data submitted publicly, the FTC will have to decide whether it is better to modify the rule or issue it as is.

But the journey doesn’t stop there. Several organizations, including the US Chamber of Commerce, have threatened to sue the FTC for exceeding its mandate. Things could be held up in court for a while, and the ruling could be repealed.

Even if the FTC fails in its effort, I think there could be some positive consequences. For one, there will be more awareness around non-competes among workers. More scrutiny of employment contracts — or at least this particular clause — can be very good for workers’ negotiating power.

In addition, a failure at the FTC may finally spur Congress to prioritize regulation limiting non-competes. Much less likely, but more eyes on this issue can create political pressure.

The proposal demonstrates how economic policy has become significantly more data-driven in the last few decades, bolstered by the empirical economics revolution in academia. Empirical studies rely on strategies like natural experiments and quasi-experiments, which attempt to go beyond correlational studies and attempt to establish causation.

It might be counterintuitive that non-competes reduce prices and increase wages. But recall that non-competes restrict worker mobility and entrepreneurialism. 45% of primary care physicians can’t start a new practice in their area because they are bound by a non-compete. If non-competes were banned, new healthcare providers could get started or hire doctors. The higher level of competition would incentivize firms to reduce prices and slim down profit margins to stay competitive.

Great discussion of both sides. It's a bit ironic that other individual freedoms are held at a higher standard than freedom to work. Non-competes limit individual freedom at the benefit of "trade secrets". As you point out, trade secret laws and corporate espionage can still be prosecuted in the absence of non-competes anyway, just more burdensome for the plaintiffs to prove what's indeed a trade secret and proprietary IP.

Most of the support of non-competes relies on trusting corporations to do the right thing (train and retain their employees)... and when has that ever worked? Companies are already well protected by NDAs and trade secret laws, they don’t need non-competes! Get rid of em