How Employers Collude to Reduce Worker Pay

It started with smoke-filled back rooms. Game theory shows how private data markets and algorithms could make the problem worse

In 2017, a man named Mahesh Patel set up a meeting that he would later regret. He was an executive at Pratt & Whitney, an aerospace company that makes engines for civilian and military aircraft. Patel had been searching for ways to retain engineers at the company, and finally figured out a creative way to do it.

He decided to get together his rivals — executives at 5 outsourcing companies who also hired aerospace engineers — and ask them to agree not to poach each others’ workers. That way workers wouldn’t be able to shop around for better jobs, and have no choice but to stay at their company. Cost savings for everyone!

Patel’s counterparts agreed. So he became a sort of mob boss, with other executives telling him if companies fell out of line. As one exec tattled to Patel:

“I am very concerned that [redacted company] believes they can hire any of our employees .... Could you please stop this person from being hired by [redacted company]?”

Unfortunately for Patel and his pals, this is textbook employer collusion, which is illegal under US antitrust law. The Justice Department brought a criminal no-poach case against them in late 2021, and they are now awaiting trial. On the line: a fines of up to 2x the harm done to employees in terms of lost wages, and 10 years in prison.

Looks like there are good meetings, bad meetings, and… really bad meetings.

In the antitrust context, collusion is when two or more parties agree to limit open competition. It can happen for a variety of things like price fixing, dividing up a market for different competitors, or limiting production of a good or service. In the case of employment-related collusion, workers are the ones that are economically harmed.

In this piece we’ll explore different types of employer collusion, the game theory that explains why it happens, and how antitrust law has been used to stop it. We’ll also address how wage-setting algorithms could make tacit collusion even worse, and pose a huge risk for competitive markets.

Types of Employer Collusion

In 2016, the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission jointly issued guidance for Human Resources professionals on what would be considered illegal under antitrust laws:

Wage-fixing1: if one company agrees with another about salary or compensation for workers, whether a fixed amount or in a range. Directly sets a ceiling on worker pay.

No-poaching: if one company agrees with another about refusing to solicit or hire each other’s employees. Indirectly sets a ceiling on worker pay by undermining their alternative employment options.

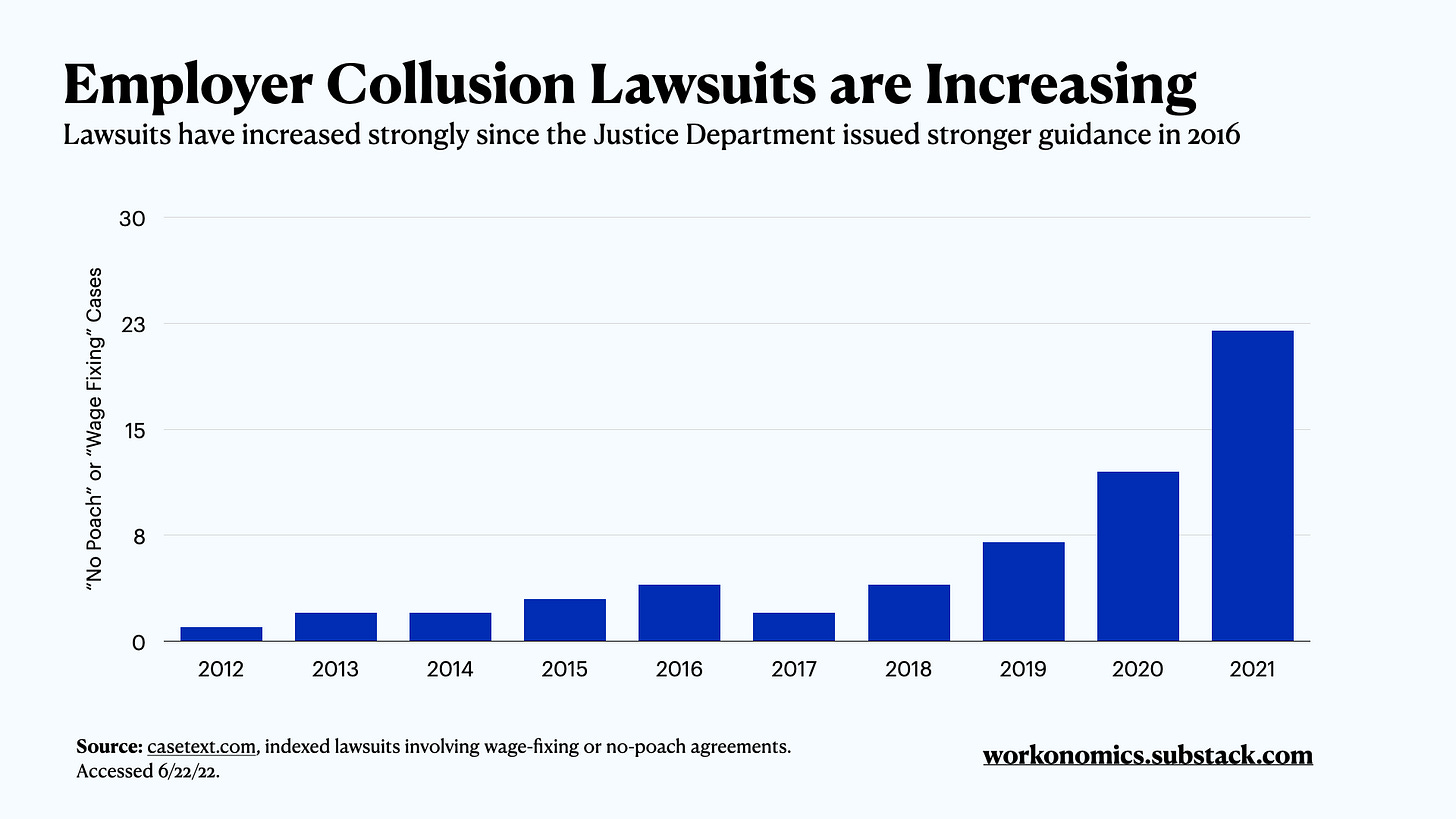

Several agreements have been uncovered over the years, across a variety of industries and both low-wage and high-wage workers. Particularly during the Biden Administration, the FTC and Justice Department have taken a much more aggressive stance on filing criminal charges for employer collusion. In these cases, companies that are found guilty would be liable to pay fines and in some cases executives could go to prison.

Here are a few noteworthy cases:

2011: Lucasfilm and Pixar (which were competitors at the time2) were found guilty of making wage-fixing and no-poaching agreements, agreeing not to solicit each other’s digital animators, and to cap salaries in certain cases. In a related class-action suit, the companies settled with workers for $100M.

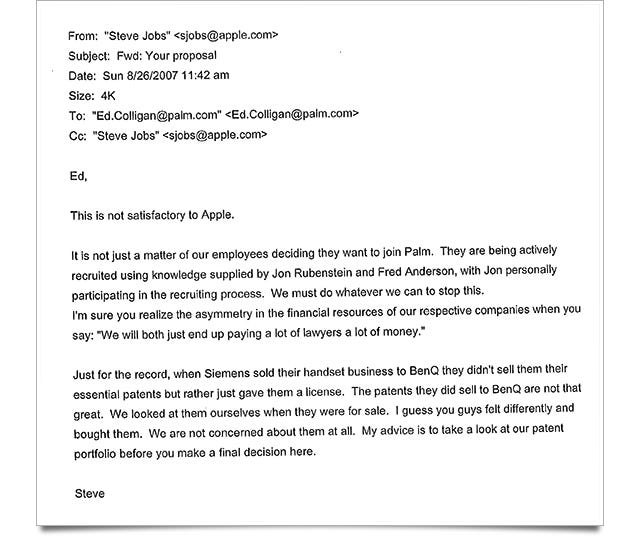

2011: Adobe, Apple, Google, Intuit, Intel, and Pixar were found guilty of making a web of no-poach agreements, agreeing not to cold-call each others’ employees for recruiting purposes. The companies settled for $415M.

2019: 20 poultry producers (including Tyson Foods) covering 90% of the poultry market, were indicted for making wage-fixing agreements, by sharing detailed compensation information with each other about hourly livestock workers (ongoing trial)

2021: Health care staffing companies in Nevada were indicted for making both wage-fixing and no-poach agreements, agreeing not to hire each others nurses and suppress their wages. The defendants are close to reaching a plea deal, which if so would represent the first criminal case against employer antitrust violations (ongoing trial)

2022: 4 home healthcare agencies were indicted for making wage-fixing and no-poach agreements for some essential healthcare workers during COVID, by fixing hourly pay and agreeing not to hire each others’ workers (ongoing trial)

Why Collusion Happens

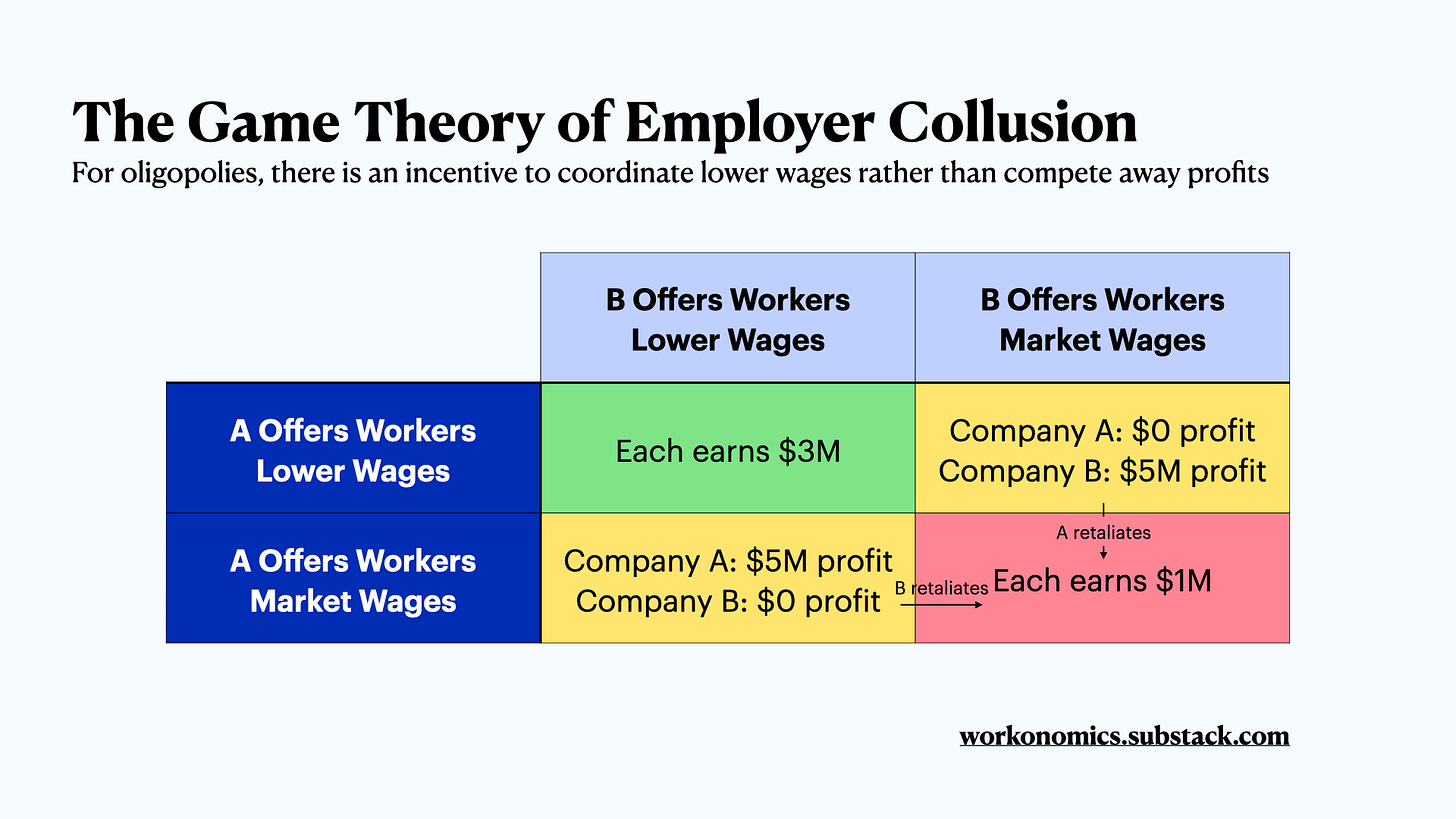

Collusion hinges on all parties cooperating together. If just one of the parties defects, then the whole thing falls apart.

For example, if the owners of a bunch of fast food restaurants in a town agree that they won’t pay more than $10/hr for their workers, that would be effective collusion in the form of wage-fixing. But if one restaurant decides to defect and raise wages to $15/hr, then all of the fast food workers would try to get hired there. Competitors would have no choice but to retaliate and match the high wages, and the the collusive agreement would fall apart.

This, of course, is not ideal for the companies, as it harms their profitability. The situation is captured in the game theory payoff matrix below:

Collusion is more likely for companies in certain situations:

Easy to coordinate. In situations where there are few competitors (e.g. cell phone carriers), it’s potentially easy to get everyone in a room to come to some agreement. Similarly, it can be easy to coordinate if a small number of people own all the competitors in a market (e.g. car dealerships in a small town).3

Strong incentives to agree/stay in agreement. If collusion has the potential to make or break the business — allowing it to turn a profit, for instance — then companies have strong incentives to collude. In this situation, colluding companies also have a strong incentive not to defect and break the agreement unless they want to tank their business.

Low chance / small penalties if caught. People jay walk all the time because there is a small chance of getting in trouble. Similarly, employers would be more likely to collude if there’s less scrutiny — like if they’re in a small town that’s unlikely to be investigated by the FTC, or if they have a secure line of communication that leaves no trace.

Tacit Collusion

What if companies don’t make an explicit agreement to wage fix or to not poach each others’ employees? This is the world of tacit collusion. Without some sort of written record of an agreement, it is much harder for the Justice Department to prosecute cases. But importantly, the effects of tacit collusion can be similar or the same as explicit collusion agreements.

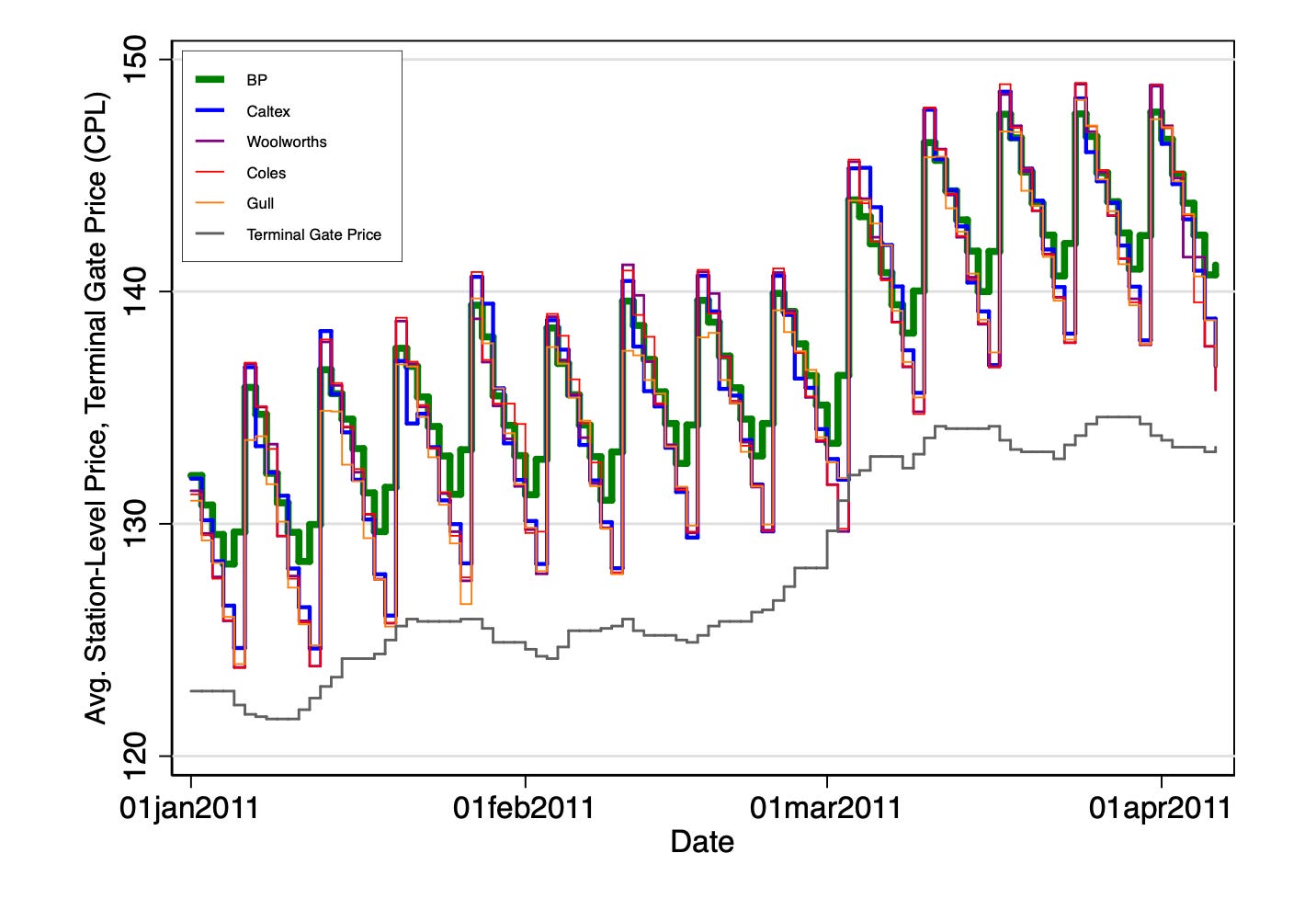

Take a study of gas stations in Australia, for instance. Multiple gas stations, at least in theory, would compete with each other to offer the lowest possible price for gas — as close as possible to the true cost of the commodity (‘Terminal Gate Price’ in the chart below). But as the study authors observed, the largest gas company — BP — would on a weekly basis hike prices at its stations to a level where it would reap a larger profit. And other gas stations, realizing it would also benefit them more, followed suit. Eventually companies would start lowering their price again (a temporary breaking down of the tacit collusion),4 and then the cycle would eventually repeat.

This example is tacit collusion over price (price-fixing), but the same sort of logic could hold with tacit fixing of wages. A dominant market player could exercise their market strength to hold back wages for a class of workers. If the conditions are right (e.g. high consolidation, low profits), other competitors may follow in doing the same.

The Risk of Data Markets and Algorithms

Even as the Justice Department ramps up its criminal lawsuits against companies where there is direct evidence of collusion, technology may actually make the problem worse. Directly sharing compensation data with competitors is illegal as it can, of course, lead to collusion.5 But with the proliferation of data markets and expansion of data science capabilities to more companies, employers may be able to get competitor data through other means.

For example, Bloomberg’s Second Measure is a business that packages anonymized credit card and bank transaction data for millions of US consumers and resells it to companies. Gig companies like Instacart and Doordash are listed on the site as customers, and presumably use it to keep track of their competitors pricing and wage trends. Instead of gig companies sharing compensation data with each other directly (which, again, would be illegal) they can all buy a sample of it from this third-party service, and use data science to estimate the rest. Problem solved!

In addition to competitor data becoming more accessible, using algorithms can be a major risk factor for tacit collusion.6 Gig companies use algorithms to determine worker compensation, but this practice is already extending to other traditional employers.

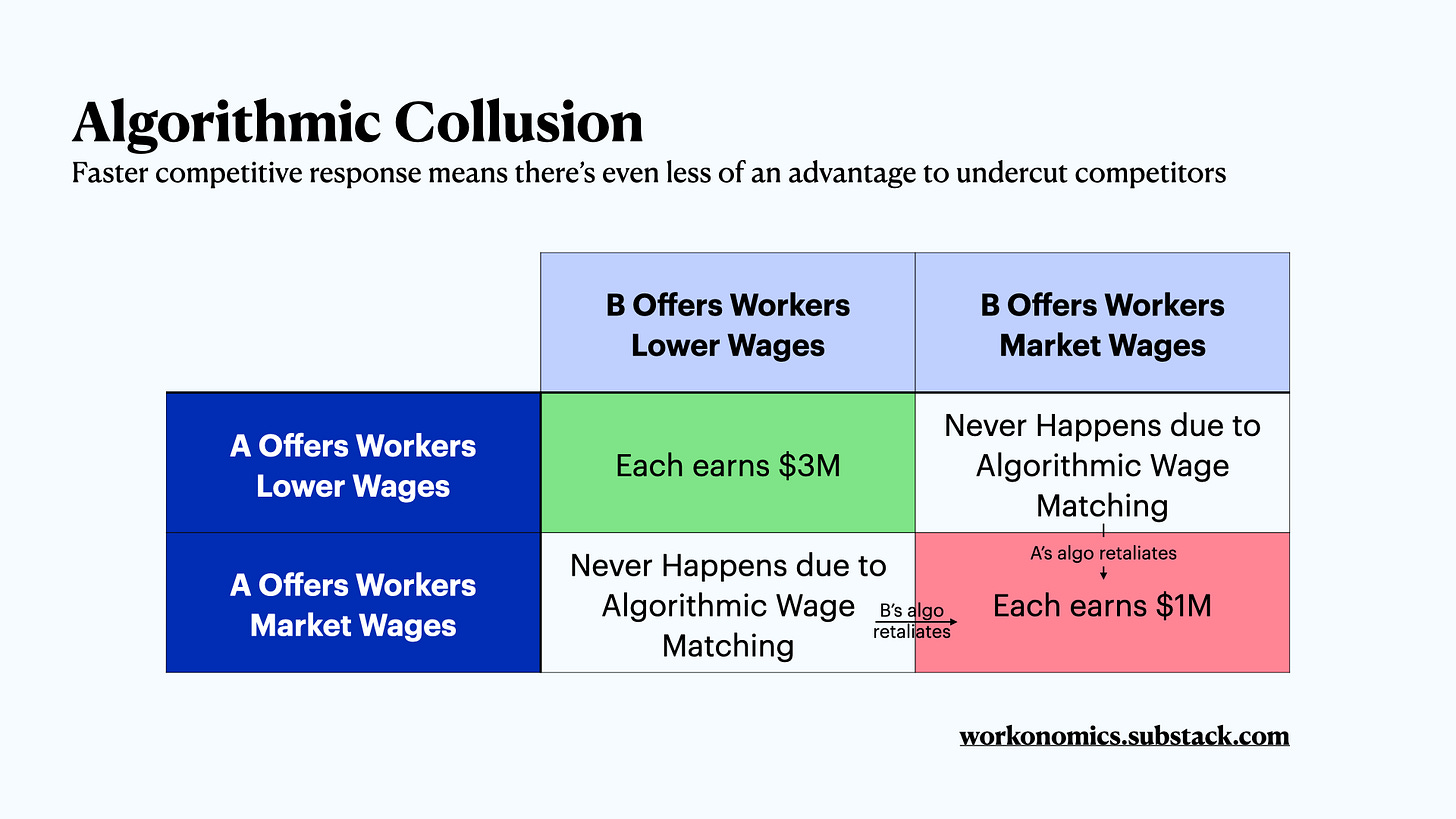

Game theory helps explain why algorithms pose such a risk. If companies use algorithms to calculate worker wages or salary, they would react even more quickly than they do now to changes in competitor strategy and wages. This changes the game theory payoffs of choosing to defect (and be competitive on wages) vs choosing to cooperate (and holding wages down).

So wage-setting algorithms may avoid increasing wages out of a decision to avoid triggering a ‘wage war’ with highly vigilant competitors. This ‘tit-for-tat’ strategy has shown to be extremely effective in repeated prisoner’s dilemma games, so rational employers would probably choose to adopt it (without any back room meeting needing to take place!)

Conclusions

Overall, the Justice Department’s increasing interventions in employer collusion cases is great news for workers. It means that workers will have more alternatives for work and, assuming perfect competition, these alternatives will pay more.

We can’t stop there. The game has changed, and antitrust laws need to be revisited to account for emergent forms of tacit collusion. Regulators in the US, UK, and EU are already eyeing algorithmic collusion as a threat to current antitrust law. New laws could reduce employer collusion risk and protect workers by, for example, requiring companies to disclose more wage data, be more transparent on how their wage algorithms work, or even ban wage algorithms from using certain types of inputs (e.g. competitor data) entirely.

We are in the middle of the data age where information is power. We should acknowledge that the game has changed, and make sure that workers and companies are on an equal playing field. ▽

Thank you to Tadas Antanavicius, Oscar Rivera, Jess Rollen, and Seb Rollen for reading drafts of this essay and providing feedback.

It’s also important to know that wage-fixing can also take place through non-collusive means. For example, in June 2022, there was a class-action lawsuit against Uber and Lyft for ‘vertical’ wage fixing, where the companies set the wages directly for drivers and hold them down even while increasing rider prices.

Disney (which owned Pixar since 2006) also acquired Lucasfilm in 2012, consolidating the market for skilled digital animators and thereby reducing their bargaining power. Notably, a lawsuit concerning Disney’s no-poach polices prior to that acquisition surfaced employees lost at least $300M in wages due to those agreements. No-poach agreements within a company’s divisions are not illegal under current law.

One particular reason for industry consolidation is that common ownership of competing firms gives the owners better pricing power (in the form of higher consumer prices, or lower worker wages).

One might argue that this is not stable collusion between the companies. But if even part of the time there is collusive activity, there is still collusive activity.

Direct sharing of compensation data is illegal, but the FTC has established an ‘antitrust safety zone’ for industry compensation surveys if they meet a few criteria. Those criteria include the survey being managed by a third party, only publishing data that is from 3+ months prior, ensuring that 5+ employers report on each statistic, and not identifying any one company for any specific information.