The Health of the Labor Market | Roundup #6

As Guy Berger puts it, "the market is letting off steam but the water is still hot"

This is a weekly roundup where I share the most interesting articles, quotes, charts, or other tidbits from what I’ve read in labor topics the past week. If you’re trying to quickly come up-to-date on news in labor policy, economics, and how technology is affecting workers, this is for you.

Also — I’ll be skipping next week’s update as I’ll be at a wedding. Hopefully nothing big happens that week.

On to the update!

Assessing the Health of the Labor Market

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics, part of the Department of Labor, released its monthly jobs update on Friday. The report has been especially important lately given its implications for future Federal Reserve decisions. Fed Chair Jerome Powell has been eyeing the labor market as he increases interest rates, as he believes that high wage growth has been contributing to inflation.

I’ll hold off on discussing the this theory1 and its validity more in depth, as that could warrant a longer post and more expert views. But this has real implications for everyone — even though increasing interest rates can help bring down inflation, it will come at the cost of lower wage growth and higher unemployment.

But where is the labor market right now and what does it mean? Linkedin Principal Economist Guy Berger summed it up quite well when he said:

“The boiling-hot labor market is letting off a little bit of steam, but the water is still hot,” said Guy Berger, principal economist at LinkedIn. “The real dream for the Fed is that this continues — that job growth remains strong but underlying inflation comes down…

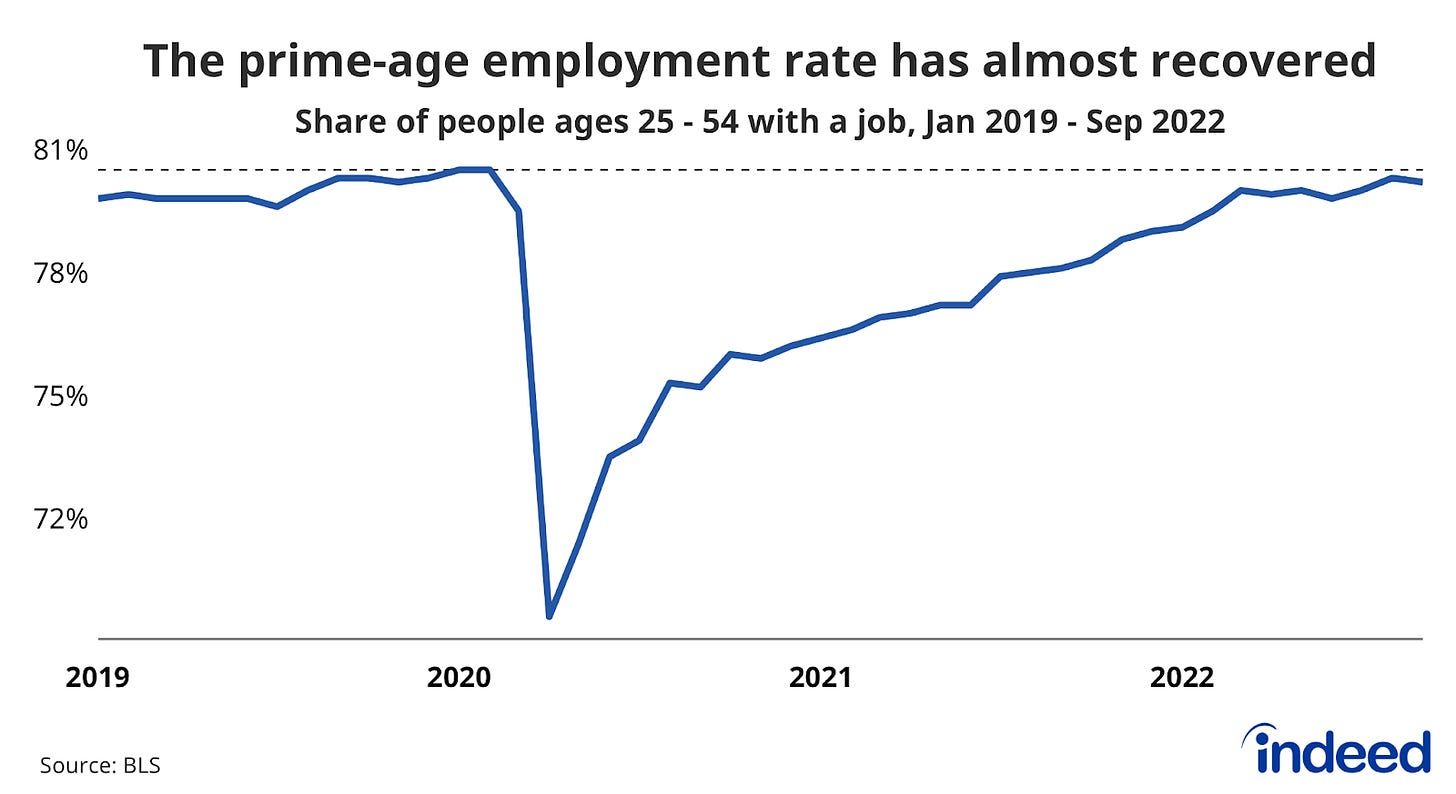

Let’s break this analogy down. To see how the ‘water is still hot,’ we should look at total employment statistics. Here, we won’t look at the unemployment rate, but rather at another number called the prime age employment to population ratio (PAEPOP), the share of adults aged 25-54 with a job.2

PAEPOP is less affected by short term and seasonal fluctuations in the labor market than the unemployment rate is, and it’s a more reliable indicator of the overall health of the labor market. For more about why PAEPOP is a better indicator than the unemployment rate, check out this incredible Twitter thread from Joey Politano.

Anyway, here is PAEPOP since 2019 — notice how close we are to pre-pandemic levels:

And if we zoom out, looking at PAEPOP over the last 25 years, we see how close we are to a generational high in employment:

People are working! This data offers a rebuttal for the “Americans are sitting on the sidelines, collecting their unemployment checks, and not working” theory, which some pundits are quick to propose.

OK, so the water is still hot. But where is the ‘labor market letting off a little bit of steam’? For this we need to look at wage growth, which has slowed from its peak about a year ago:

Based on 2 different ways of calculating wage growth, it appears to be decelerating! So overall, the labor market is still strong, but it is tapering back to a steady equilibrium. This is good news if you’re someone who wants to avoid steep interest rate increases, which will increase unemployment. But the question of whether wages are slowing down fast enough is far from being settled, which might have implications for future unemployment…

Is the Labor Market Letting Off Enough Steam for the Fed?

Generally, the Fed is looking for wage growth in the neighborhood of 3.5-4% which it believes is necessary for its 2% inflation target.3 And depending on the way that the Fed is calculating wage growth, it may be closer to 5% (Y/Y method) or 4.5% (M/M, 6M Moving Avg method). So the particular way that economists are processing the data can have big implications.

On top of it, as the wage growth numbers are delayed. The Fed wants to avoid ‘overcorrecting’ and sending the country into a deep recession with low or negative wage growth. In my humble, non-expert view, it may be wise for the Fed to look at a M/M moving average, which is better at incorporating recent trends than Y/Y. Some economists are arguing these recent trends are a good reason that the Fed shouldn’t hike rates as much.

Either way you look at it, though, it looks like there are more rate increases in our future. Now the remaining question will be whether those rate increases go too far and start causing unemployment. It will be good to track how these metrics trend in the next few months so that we can adequately manage the increase in unemployment, and ensure all Americans land safely on their feet.

Noteworthy Links

Big Company Union Busting

Bloomberg: Apple Made Anti-Union Threats in Oklahoma, Complaint Alleges

Bloomberg: Starbucks Fires Activist Barista for Refusing to Remove Anti-Suicide Pin

Bloomberg: Starbucks Illegally Fired Michigan Worker Over Union Activism, Labor Board Judge Rules

Washington Post: Howard Schultz’s fight to stop a Starbucks barista uprising

Other News and Perspectives

WSJ: More Businesses Want to Hire People With Criminal Records Amid Tight Job Market

Intelligencer: The Whiny Grade-Grubbing NYU Students Have a Point

Deadline: Strippers At North Hollywood Club Will Vote On Union Representation With Actors’ Equity

The American Conservative: End the Wage Gap for the Most Essential Worker

Lapham’s Quarterly: Working Arrangement

White House: Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights

SF Gate: Restaurant workers at SFO receive raises after 3-day strike

Para: Gig Workers Can Now Accept or Decline Offers from Multiple Platforms Within One App

NYTimes: New Federal and State Bills Would Improve the Labor Rights of Garment Workers

Niskanen Center: Census poverty numbers may underestimate pandemic UI impact by half

Dean Baker: Will International Competition For Remote High-Level Jobs Be Good Or Bad?

Bloomberg Law: Justices to Mull Labor Law Preemption of Property Damage Claims

Bloomberg: US Immigration Rebounds But Remains Far From Plugging Labor Gaps

The Nation: Has Labor Become More or Less Powerful Over the Last 2 Decades

Bloomberg Law: Competition Authority Gives FTC New Tool on Gig Worker Policies

This phenomenon is often referred to as the ‘wage-price spiral’. Not all economists agree that this is happening right now, including IMF Economist John Bluedorn.

If you don’t have an upper bound on age for the employment to population ratio, you will inevitably start seeing this metric decline as more of the US population ages into retirement. You also want to set a lower bound on age as younger adults are finishing up schooling and training and so are not yet in their ‘prime employment years.’

This is more of a simplification of what the current Fed would do. The Economic Policy Institute has made the argument that wages can grow a full percentage point faster than the Fed thinks they can — 4.5-5% — and still be commensurate with their 2% long-term inflation target. But again, the debate over the Fed decision making process is a can of worms and better handled by professional economists.