Last Thursday, 33-year-old Christian Smalls testified before the Senate Budget Committee. He stood out from the Brooks Brothers suit-wearing, Harvard Law degree-holding types around him. With a Yankees fitted cap and red jacket with “Eat the Rich” emblazoned on the back, Smalls represents a different, resurgent type of political power. This man wants to unionize Amazon. All of it. Just a few weeks ago, he led thousands of workers at a Amazon fulfillment center in Staten Island to a historic victory — with a majority of workers voting in favor of establishing a union.

Unions have a lot going for them right now. With the current tight labor market, workers can command higher wages and better working conditions. Unions are a particularly good vehicle to do that, with typical union contracts boosting workers’ hourly pay by 10.2%. According to Gallup, public support for unions is at an all time high of 68%. A poll by Blue Rose Research even shows 75% support the right of Amazon workers to unionize.

But Smalls and the broader organized labor movement still face strong headwinds. The Amazon union election in Staten Island is still pending a government hearing to fully certify it, with Amazon using various tactics to delay and undermine the union’s case. More broadly, union representation in the US has been long in decline, and is currently at an all time low of 10%. In 1960 it was closer to 30%. In Europe, some wealthy economies reach as high as 70%. For the labor movement, there is a long, difficult road ahead.

How well is unionization actually going right now? It can help to take a step back from the frequent news articles discussing headline union cases. Instead, we can look at union data extending from July 2011 to today, and get a more informed overview of how things are going. In this post, we’ll take a look at this data, and understand:

Historical trends in union success rate, union membership

How the size of a union impacts its success

Which states tend to see higher rates of unionization

Brief Note on Methodology

I analyzed 13,516 union certification cases filed with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the government body that oversees elections for union representation. These cases extend from July 1, 2011 to May 6, 2022. I only considered cases where a formal certification decision from the Board was delivered, either a:

Certification of Representation: when a union wins. A majority of workers voted in favor for the union at their bargaining site (typically, an individual retail location, factory, or warehouse). The NLRB certified that the union now has collective bargaining rights with the employer in question.

Certification of Results: when the union loses. The NLRB certifies that the union did not receive the required majority of worker votes to unionize, and therefore cannot represent the workers.

The Amazon fulfillment center in Staten Island and several Starbucks had a union election held but the NLRB had not yet certified it, so they were excluded from this analysis. 18 out of 40 Starbucks union cases had received a final certification from the NLRB as of this analysis and so were included.

It’s also important to note that this analysis is not comprehensive — I didn’t look at dismissed or withdrawn union petitions, for example. The NLRB also holds other types of elections, like union no-confidence or decertification that would remove bargaining rights from a union. These comprise a smaller number of NLRB union representation petitions, but would still be interesting to investigate in a future post.

What follows is a few key insights from looking at more than 10 years of union election data.

1. Union certification decisions have not recovered from COVID

Once COVID hit in March 2020, unemployment skyrocketed to almost 15%. Hospitality, travel, and other industries lost significant business, and workers in those industries ran out of options. This was not an ideal time to unionize. As a result, the number of union certification decisions dropped.

The economy has mostly recovered, with unemployment now at 3.6%, a historical low. But somewhat mysteriously, union certification decisions have not quite recovered to pre-COVID levels. Matt Darling, Employment Policy Fellow at the Niskanen Institute, underscored the point that the ‘huge union wave’ often discussed in the media hasn’t materialized in terms of actual union filings yet.

One reason for stagnation may be that Democrats didn’t obtain majority control of the NLRB until August 2021. The new board has a big backlog to work through, and — infamously — the NLRB has been notoriously underfunded, with no budget increase since 2014. Without a sufficient number of lawyers and staff to work through all the cases, there will naturally be a cap on how fast unionization can happen.

There is a silver lining here. There are more than 14,000 workers in union cases opened in 2022 that are still pending with the NLRB, including the 8,325 workers at the Amazon fulfillment center in Staten Island whose union case is still pending.1 If just the one Amazon union gets approved, Q2 2022 would certainly mark a return to the pre-pandemic trend, if not also the promise of exceeding it.

2. An increasing percentage of union certifications are won by the union

In 2012-13, around 60% of union election cases brought before the NLRB ended up in the union getting legally certified to be the employees’ bargaining representative. But by 2019, the percentage had crept up to 73%. Interestingly, this was in spite of the Trump administration installing more conservative members onto the NLRB.

Recent data from 2022 seems to confirm that we are back on this trend, indicating a successful certification rate around 74%, a 10-year record. This could be due to a few reasons. One is that the environment is shifting to be more pro-union, with a President who sings organized labor’s praises, and now a Democratic majority on the NLRB. The momentum of the Amazon and Starbucks union petitions could be helping rally union support more broadly. Lastly, workers may simply have more of an incentive to vote for their union in the current economic environment. Inflation in excess of 8% means workers’ living standards are dropping quickly, and a union contract could help protect their wages from cost increases.

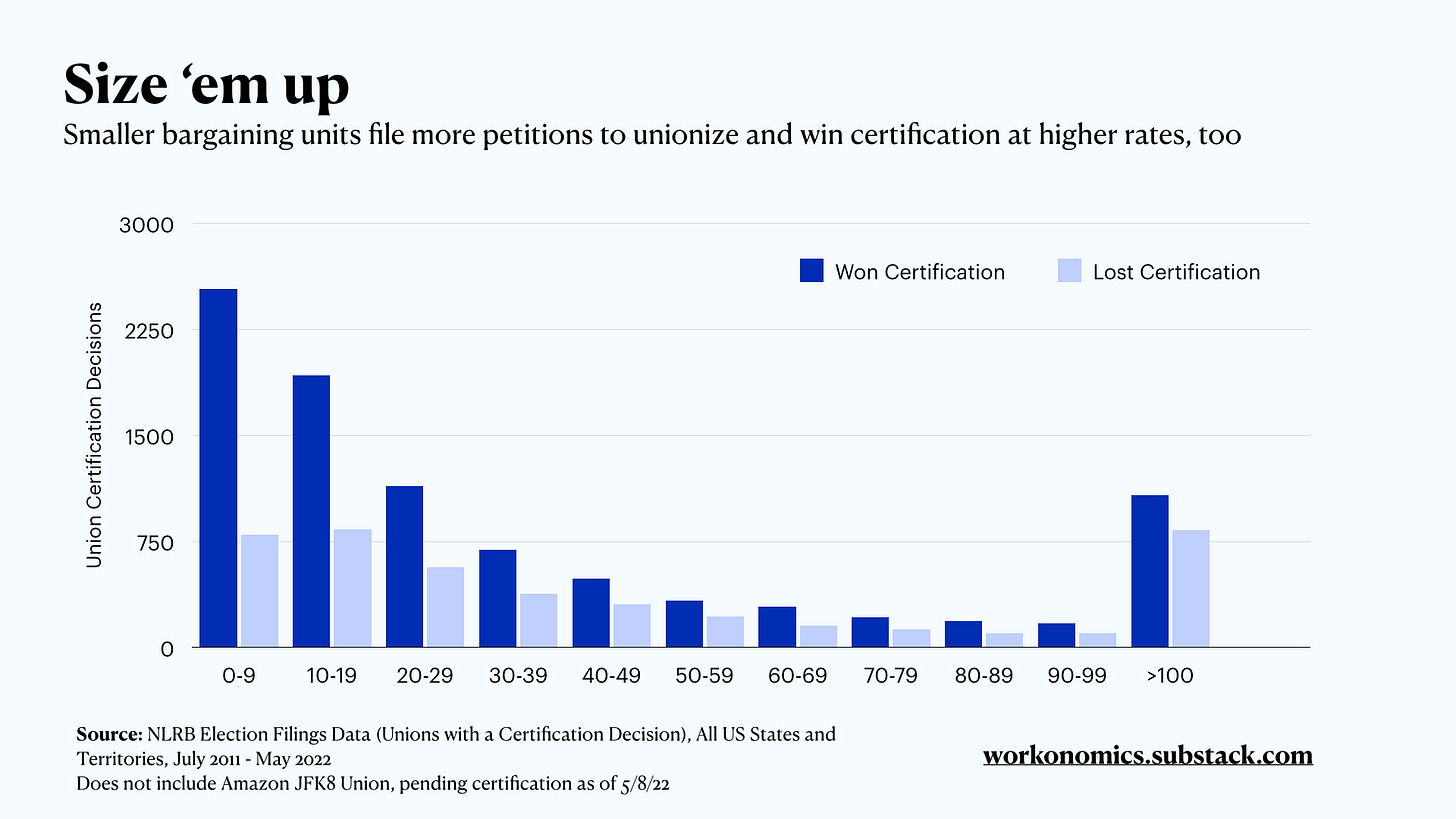

3. Smaller union petitions have been more successful

For unions, apparently size really matters. When looking at data from the past decade in aggregate, most new union petitions are for relatively small bargaining units (<30 workers). It is also true that smaller union petitions have a higher success rate: 76% of union petitions with less than 10 workers successfully get certified, while only 56% of petitions with greater than 100 workers are successful.

The exact reasons are unclear. Smaller unions are of course more nimble — and its easier to get on the same page with your fellow workers if you know all of them. But a bigger reason may be that larger unions will often run up against employers with strong legal teams and a willingness to invest in anti-union consultants.

Does this mean that putting more institutional and financial support behind small unions would be more effective than a really large union campaign? Perhaps. But it would also seem that the largest gains from collective bargaining would come from negotiating with large companies that historically have had massive wage-setting power over its workers. Moreover, in terms of the number of actual unionized workers, one successful petition for a very large union may be worth hundreds of small unions — so the higher failure rate may be justified. See below for why large unions are so important for increasing worker representation.

There are reasons to pursue both sides of the spectrum.

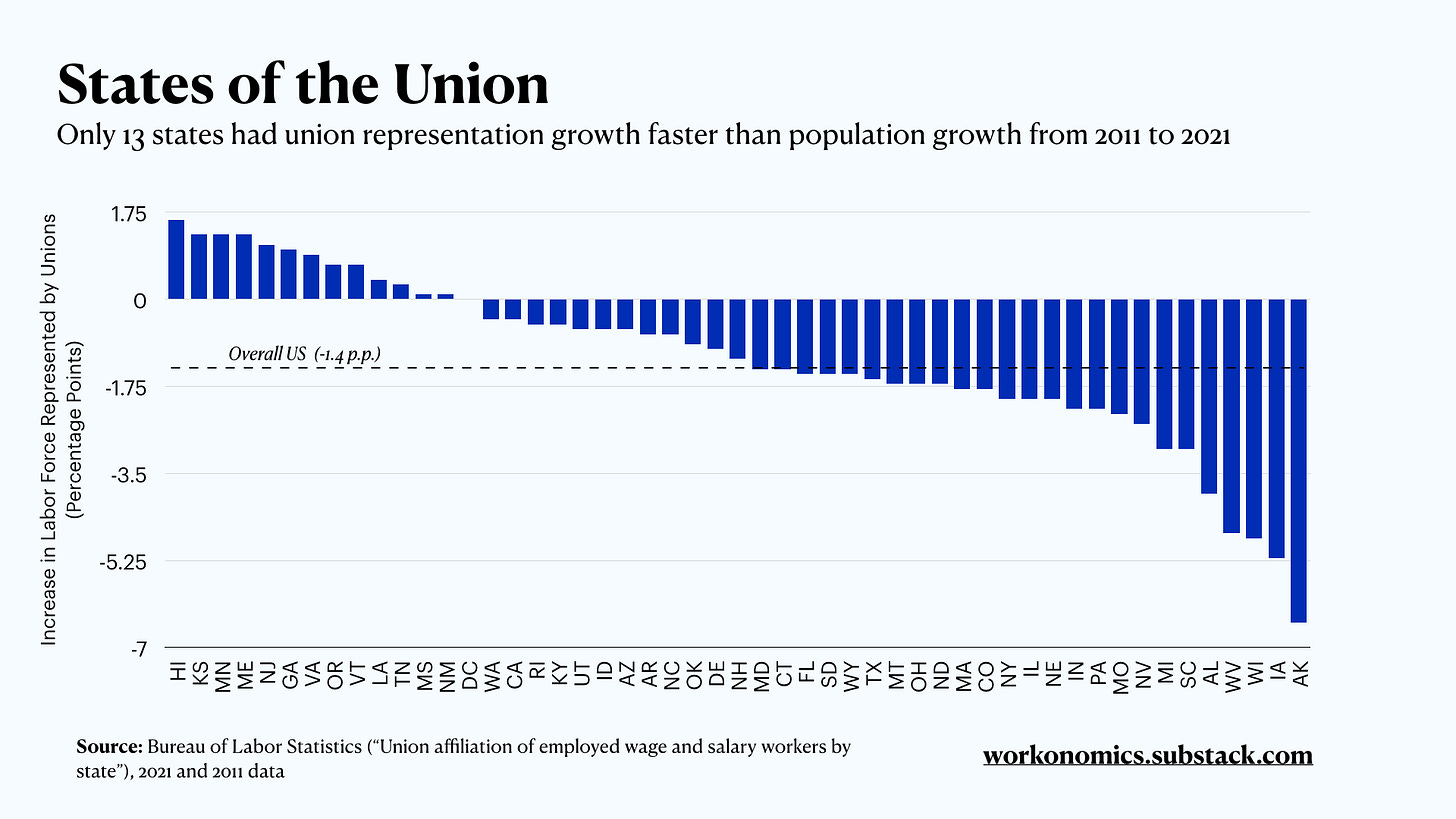

4. Union density declined across most states

From 2011 to 2021, only 21 states and DC increased the absolute number of workers covered by a union. Interestingly, 3 west coast states — California, Washington, and Oregon — emerge in the top 5.

But these absolute numbers obscures a more important truth. California and Washington actually had a decrease in the proportion of the workforce represented by unions, because the populations grew faster than unions did. Only 13 states had union representation grow faster than population growth. Hawaii, Kansas, Minnesota, Maine, and New Jersey stood out in terms of unionization momentum.

So maybe the the west coast isn’t the best coast after all.

These states where unionization is becoming denser aren’t nearly as covered in national media as are big ones like California and New York, which have big headline union fights. But if you assumed the rest of the US grew their union representation percentage at the average clip of those top 5 states, you would have increased union representation by nearly 4 million workers, a 24% increase from where it is now. Talk about a movement in organized labor.

Conclusions

Unions are, like any organization, constrained by time and money. Adversarial corporations have deep pockets and sophisticated legal teams that can make it difficult even for the best organized workers to organize. For an effective labor movement, there must be good data to rely on so that unions can make informed decisions and allocate these limited resources effectively.

This was a pretty preliminary analysis of union elections and their results. It’s clear that there is a lot of work cut out for the labor movement, such as the fact unionization is still below pre-COVID levels. There are also some bright spots in the last decade, like small union successes, or the dense unionization in places like Hawaii, Kansas, and Minnesota. Further research on the causal mechanisms of union election success is warranted, and can help labor efforts everywhere. It is high time to dig into the data.

A NLRB hearing on the Amazon Staten Island union case is expected for June 2022.