The Legal Definition of "Work Time" in New Gig Worker Laws Is Utterly Confusing

It puts the onus on drivers to determine how benefits apply

When is a gig worker working? Is it only when they’re driving with people or goods in their car? What about time when they’re on their way to a pickup, especially if it’s in a different neighborhood or city? And what about so-called ‘idle time,’ when a worker is available to accept a job?

The answer, if you look closely at the state-level laws in place in California and Washington, is: all of them, maybe… sometimes? The law has effectively equivocated by using different definitions for ‘working time’ for different purposes, and in different states. As a result, this has created a labyrinth of laws that gig workers need to navigate to understand what they’re entitled to.

There are several other issues with these laws, such as Washington’s preemption of local laws on gig workers, the poor state of healthcare benefits, and California requiring a supermajority to amend its law. But in this article, we’ll investigate some of these big discrepancies in the way that ‘working time’ is defined across and within these laws.

A Brief Breakdown of Work Time

Researchers have already documented the different components of work time for active drivers (once they mark that they are “Online” on their app). For example, in order for Seattle to set minimum pay standards for rideshare companies in 2020, it commissioned an academic study of rideshare drivers and their effective pay. We can glean a lot of interesting statistics from it. As expected, nearly half of drivers’ time is spent in passenger time, or time when the passenger is physically in their car. The other half of the time is formed by dispatch time (when a driver has accepted a trip and is en-route to a pickup) and platform time (when a driver is available but in between trips).

It’s clear to most observers that passenger and dispatch time is actual work time. Platform time is a bit more controversial, since people may think that drivers can be doing anything during this time. But on closer inspection, its clear that drivers are working during this time too. To stay ‘online,’ and therefore continue accruing platform time, Uber drivers must respond to all dispatch requests (within a few seconds) as they come up on their app and can’t reject more than 2 requests in a row. Drivers have every incentive to use that time to figure out where to get more dispatches or drive their car from a low-demand to high-demand area. So platform time definitely seems to qualify as work time, time that drivers labor to increase the productivity of rideshare platforms.

Comparing The Laws’ Definitions of Work Time

Despite many people thinking of Proposition 22 and HB 2076 as clones of each other, they in reality have several differences. Moreover, they have several discrepancies within themselves — especially in terms of the definition of working time used across the different benefit statutes (e.g. the Minimum Pay Guarantee, Paid Sick Leave, and Workers’ Compensation benefits).

Taking a closer look at these 3 particular statutes and their associated assumptions can help us design better policies for gig workers in the future.

Minimum Pay Guarantee

Per-Minute Minimums. California pays out drivers a minimum per-minute rate based on passenger and dispatch time, accounting for 62% of the total driver working time. Using this definition of working time, the California law promises to pay drivers 120% of the local minimum wage standard, which in California would be $0.30-$0.34/min depending on the city. While ostensibly better than minimum wage, 120% wouldn’t fully compensate drivers for the remaining ~38% of platform time they don’t get paid out on [0]. A pay guarantee (paid out on passenger and dispatch time) that accounted for this platform time would be closer to 161% of minimum wage.

On the other hand, Washington’s pay guarantee pays out only during passenger time. While on the surface this may seem less generous than California because it excludes dispatch time, the Washington per-minute rate actually factors in a driver’s estimated dispatch and platform time (using the driver averages from the Seattle-commissioned study, shown above). As a result, even though they are only paid out on passenger time, drivers should on average be taking home minimum wage for all their working time.

Per-Mile Minimums. Drivers incur a variety of costs while working, like gas, maintenance, and having a cellphone, that they pay for out of pocket. Both states try to help reimburse drivers for these costs, to varying extents. In some ways, this marks a major difference between typical minimum wage laws for employees (which just focus on time worked). For independent contractors, the intensity of the work (as a proxy for worker costs) also matters.

The difference between the two states is like night and day: California’s paltry $0.30/mile minimum rate compared to Washington’s $1.17/mile rate ($1.38/mile in larger cities like Seattle). Washington factors in costs over all working miles driven, while California excludes platform miles. Washington’s policy would effectively cover all of an average driver’s expenses, including car payments for a vehicle, gas, maintenance, insurance, health insurance, cellphone plan and payments, licensing, and taxes.

Issues that remain. Washington’s pay statutes, while better than California’s, do have a few issues though:

Averages assumed for everyone: The legislation assumes that all drivers’ dispatch and platform time is roughly 51% of their working time (taken from the Seattle data, see above). This may not be a great assumption for drivers in suburbs, who may have lower “time utilization” due to lower market density. A better policy would take into account these geographic differences in utilization rather than applying an average to everyone across the state. Others suggest moving away from a piecemeal payment system (only paying drivers during passenger time) to a more comprehensive wage system that compensates drivers for platform time if it doesn’t result in a trip.

Conservative rate reassessment and increases: The Seattle ordinance that Washington borrowed from here included a stipulation to annually re-estimate driver costs, utilization rates, and minimum wage — which are inputs into the per-minute and per-mile rates. This would directly account for Seattle drivers’ actual inflation. It would also incentive platforms to better utilize drivers and decrease platform time. In contrast, Washington is basing all assumptions on 2020 and now effectively tying increases to national inflation measures [1]. As a result, there is a risk that the rates wouldn’t properly account for changing driver costs and utilization.

Paid Sick Leave

Whereas California skirts paid sick leave for workers, Washington managed to offer drivers a meagre version of the states employee sick leave program for drivers. Just like employees, drivers can earn 1 hour in paid sick leave for every 40 hours worked — but this only counting passenger time. This comes as a bit of a surprise as the pay guarantee attempted to factor in all working time. The blatant disregard for the other 51% of hours drivers work means that these workers will be accumulating paid sick leave at half the rate they should be.

Workers’ Compensation

Here things get a little confusing. Let’s first look at California’s law. California offers to give all workers occupational accident insurance (OAI), which is different from standard workers’ comp in a few ways. California’s own worker’s compensation program covers the costs and lost wages from injuries and occupational diseases. The program compensates workers for different levels of permanent disability (i.e. weekly payments to replace lost wages). And there is no cost cap to workers’ compensation.

There OAI offered in California’s law does cover all of driver working time, in contrast to many of the other California policies. But still, there several reasons this OAI is subpar to workers’ compensation:

Vague Coverage of Illnesses. OAI covers injuries but doesn’t clarify whether it covers illnesses (leaving the door open for costly legal battles)

Disability Payments Capped. The policy would stop payments after 2 years even if the condition is permanent.

$1m Limit. This may appear to be a large number, but oftentimes catastrophic injury (and associated follow up care) can exceed this cost, hanging drivers out to dry.

Washington, in contrast, forces companies to enroll its workers in the state-run worker’s compensation program — with its more generous coverage of injuries and illness, higher payment limits, and permanent disability compensation. But it only covers passenger time, ignoring 51% of working time spent on dispatch and platform time.

In an unexpected way, the California and Washington catastrophic insurance policies appear to have opposite problems: California’s insurance is less generous but applies to all driver working time, Washington’s is way more generous but applies to only half of drivers’ working hours.

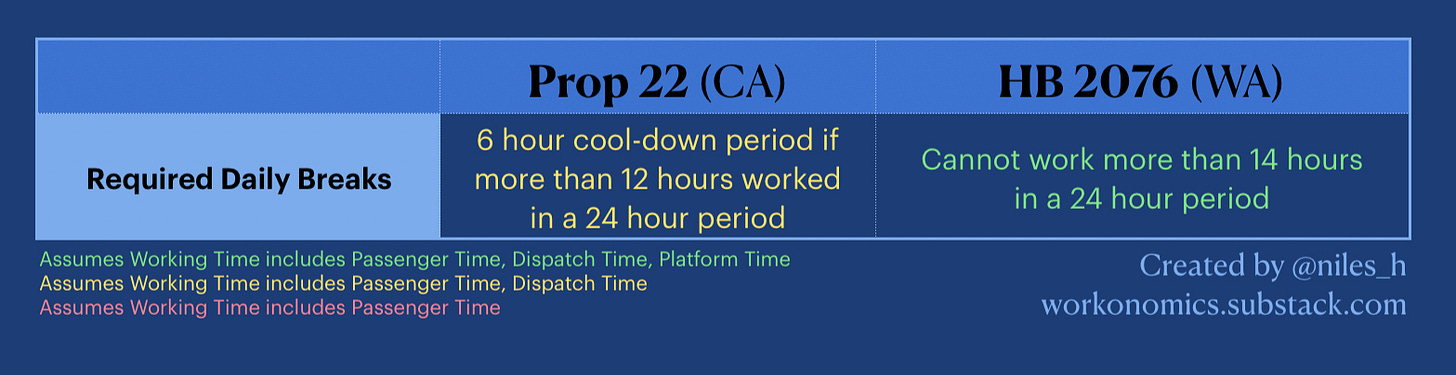

Mandatory Breaks

Under California’s law, drivers need to take a 6 hour “cool-down” period after 12 hours in passenger or dispatch time. Given that this definition of time worked is still ignoring the 38% of platform time, the reality is that drivers could still spend 19 hours working in a 24 hour period before being forced to take a break.

In contrast, Washington’s law mandates that a driver can only work 14 hours in a 24 hour period (counting all working time). Given the purpose is to improve driver and rider safety by making sure drivers get appropriate rest, this is a better designed policy compared to the California law. Even so, Washington’s 14 hour days still could mean drivers could drive for up to 98 hours a week. Employees get paid overtime wages (1.5x) after working 40 hours in a week. There is still no policy requiring rideshare companies to appropriately compensate drivers for their above-and-beyond commitment to the platform.

Conclusion

While we weren’t able to dive into each statute of Washington and California’s laws, we did see how ‘working time’ has been a malleable concept in both bills. Workers need to have intimate context of what portions of their working time their benefits apply to, and companies need to manage a patchwork of different policies, making things confusing for everyone.

Washington did mark a step forward from the extremely conservative assumptions in California’s current law. But there is still much to be desired — like the egregious fact that paid sick leave accrues at half the rate it should for workers. One clear step in the right direction is to report to drivers the total amount of time they worked, broken down by passenger, dispatch and platform time. This could allow drivers to know their actual effective compensation, and empower them to make better financial decisions of which platform to work with. And to ensure fair treatment as a bare minimum for all workers, we need to consider legislation that appropriately compensates gig workers for all working time.

Thank you to Maddy Varner and and Oscar Rivera for reading drafts of this essay.

See below for a more comprehensive summary on the statutes of the California and Washington bills, and what is defined as ‘working time’ for each statute.

Footnotes

[0] The 38% of driver platform time measured in the Seattle study comports pretty closely to a similar study in California, which estimated driver platform time at 35%.

[1] The Washington per-mile rates are tied to growth in the state minimum wage, which in turn is tied to CPI-W growth, or national inflation growth for urban wage earners and clerical workers. California, on the other hand, uses CPI-U growth, or national inflation growth for all urban customers. National CPI-W and CPI-U may not differ much, but it appears that Western metro areas (like San Francisco and Seattle) have higher inflation growth than the national average.